We live on Vancouver Island in Canada, where our Russian “Egypt” and “Turkey” are Canadian Mexico and the Dominican Republic. It was fascinating to observe how Canadian schoolchildren vacation compared to their Russian counterparts.

When school breaks begin in Canada (especially winter or spring breaks—March Break), entire families flock to the Caribbean. Sometimes, entire planes are filled with classmates and teachers heading to warmer destinations.

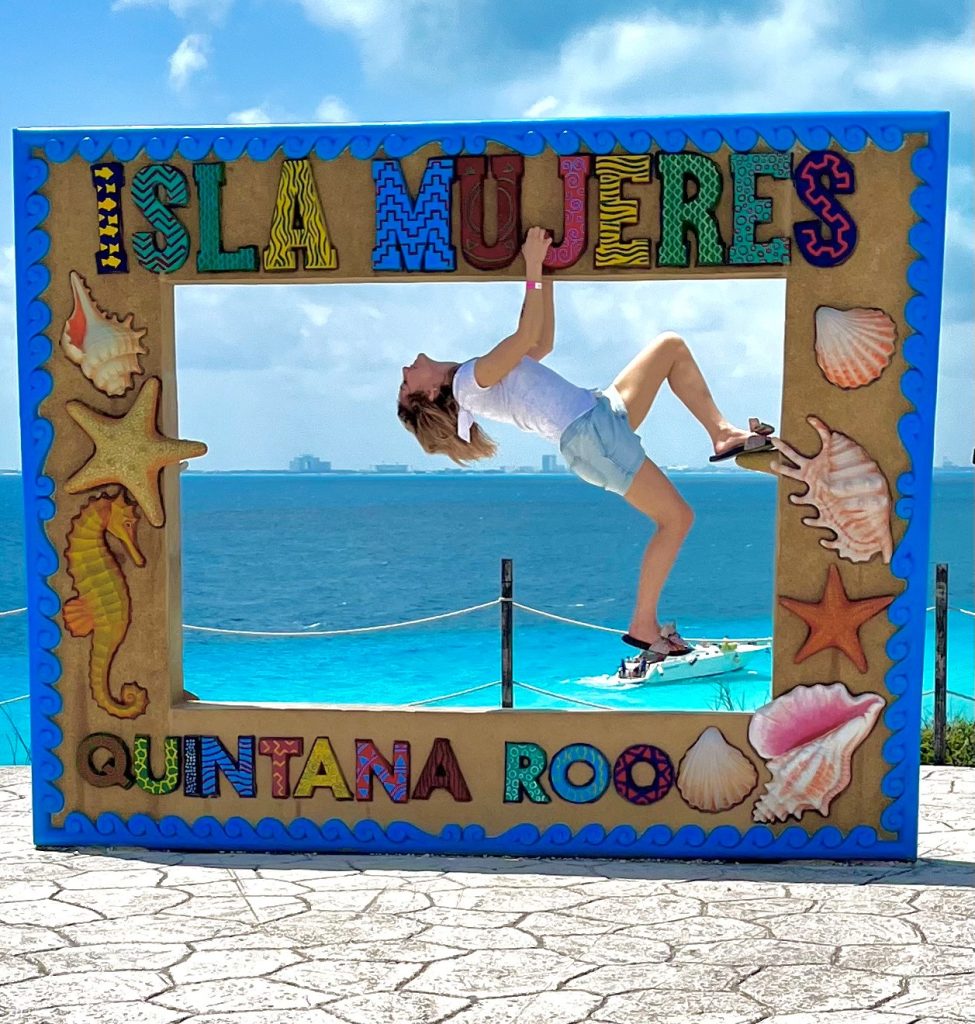

My teenage daughter and I traveled to Mexico, to Isla Mujeres—the “Island of Women,” named for ancient times when women were sent here to keep them safe from pirates. Getting from our Canadian island to the Mexican one was no easy feat: ferry, taxi, plane, then in Mexico—a bus, another taxi, another ferry, and finally a golf cart to the villa.

Supporting Local

Like Russians, Canadians enjoy all-inclusive resorts and package tours. But many, perhaps even more than Russians, now prefer “authentic” travel—a modern trend where you immerse yourself in local culture, traditions, and even try to “live like a local,” using public transport and favoring small shops and cafés over global chains.

There’s no guarantee the food will be better, but Canadians like the idea of “supporting local” (a concept that gained traction during COVID and remains strong, especially amid tensions with the U.S.). Canadians are accustomed to cultural diversity at home, so they approach new experiences with respect and curiosity.

Russians, however, have a slightly different mindset. Having paid for a vacation, we expect it to meet our expectations. We’re less eager to explore the unfamiliar—this attitude is more common among millennials and younger generations, whereas in Canada, it’s been around longer.

Transportation

Taxis operate around the island, and you can always negotiate the fare—a very Russian habit. Having haggled at Egyptian and Turkish resorts, I bargained with Mexicans enthusiastically. Canadians usually accept the set price—haggling makes them uncomfortable. The exceptions are those who own property in Mexico or seasoned backpackers.

The island has a local bus connecting the north and south, but its route is a mystery even to locals. A taxi ride costs five times as much, but without Spanish, you might end up in the wrong place. Neither Russians nor Canadians are prepared for that—unless they’re really trying to save money.

The main attraction on the island is golf carts, which form slow-moving processions along the roads, taking in the Caribbean views. No license is needed. The rides are fun but terrifying—no helmets, no seatbelts. Canadians are used to golf carts, especially in British Columbia, where golf is popular. Many families own clubs—it’s about as common as Russians owning badminton rackets. For Russians, golf carts are less familiar.

Choosing a Hotel

Different people prefer different vacations. But Canadians have a clear trend toward eco-tourism—even if it’s greenwashing (when hotels market themselves as eco-friendly with minimal environmental impact, renewable energy, and natural materials). Russia has such hotels too, but we’re less willing to overpay for “eco.”

Mexico also offers radical “eco-hotels” in the jungle—basically tents with mesh instead of windows. It’s an adventure for everyone, complete with surprises: birds flying into rooms, insects, lizards, and coatis (raccoon-like creatures that love rummaging through trash).

Teenagers

Canadian teens in Mexico are a mix of freedom and adventure—they explore jungles, learn to surf. Russian schoolchildren, meanwhile, seem to follow a “program”—parents, organized activities, and a set schedule. The one thing they have in common? Parents of all nationalities sometimes get so tired they “check out,” leaving teens to their own devices.

Schools Organize “Educational Vacations”

In Canada, study-abroad programs are popular—like trips to Mexico with Spanish lessons and volunteer work. Sometimes whole classes travel together, organized by teachers and parents. Imagine: mornings spent learning Spanish, afternoons helping at a turtle sanctuary, evenings on the beach. In Russia, such programs are just emerging, mostly for university students rather than schoolkids.

Independence

Canadian parents trust their kids more. And their children are better prepared for life—schools teach them to recognize and avoid danger. Russian kids face more restrictions and skepticism. Canadians instill “I can do it myself”; Russians, “I’ll back you up.”

Canadians believe responsibility can’t be taught under strict control. Russian parents keep kids “in sight”—maybe letting them go to a waterpark with a group, but only after anxious warnings. Our overprotectiveness is cultural: “What if something happens?” “What will people think?”

Babies on the Floor

At check-in, we saw exhausted young parents place their 3-month-old on the floor, using a sweater as a mat. The baby lay there crying while they handled baggage. Yes, Canadian parents calmly put infants on public floors without fear of judgment. To them, it’s no big deal—the child is safe (literally at their feet) while they handle logistics. If there’s real danger, bystanders will report it. Practicality and reasonable freedom matter more than anxiety.

Russian parents in the same situation would likely hold the child, even if uncomfortable. Fear of judgment and overprotectiveness run deeper. Public opinion often outweighs practicality—the “what will people say” mentality still binds older generations.

Social Media Posts

Russian teens curate perfect Instagram shots—poses, filters, hashtags. Canadians post raw, unedited moments—getting stuck in mud on a golf cart, makeup-free faces, ill-fitting swimsuits. To them, social media isn’t a highlight reel but a digital diary. They laugh at their mishaps and embrace imperfection.

In Canada, self-acceptance is taught early. In Russia, the mindset is “show only your best.” Only recently has Russia seen a shift away from “flexing” perfect lives—though Gen Z is increasingly adopting Western attitudes.

Enjoying the Moment

Russians are always braced for something to go wrong. We “sleep with one eye open”—relaxing doesn’t come easily. Canadians are more carefree.

Paradox: The more a Russian pays for a trip, the more they stress about “getting their money’s worth.” Canadians spending the same just enjoy the moment. Maybe we should learn from them—how to be present, without dwelling on yesterday or tomorrow. After all, real vacation begins not when the plane lands, but when you finally let go of control.